Authors: Brahim Ramli & Emanuel Pietrobon – 21/03/2022

Could the Ukraine war lead to a new Arab Spring?

By Brahim Ramli

The war in Ukraine is having several effects in the Arab countries, especially in North Africa. While the full scale of the war’s impact on the region will become clearer in the coming weeks and months, one month after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one can note that there are immediate challenges on different levels that the region is facing. The first challenge is a geostrategic one, while the second one is more related to the economy and in particular to the agricultural sector.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has put governments across the region in a strategic bind. There’s only one state which is Syria that is genuinely pro-Putin, every other Arab state generally prioritizes its Westerns ties, and none is trying to pivot to Moscow. But this does not mean Arab states are hostile to the Kremlin for several reasons. Russia has become a strategic partner for many countries, especially after the Russian military intervention in 2015 in Syria. Moscow emerged as a critical powerbroker for the autocrats in the region. Russia’s foreign and security policy in the MENA region assumed a new dimension after the Arab Spring, with Russia becoming a major external player in the region, it has acted as a balancer and mediator in several regional controversies and has continued to serve as a security guarantor for the Syrian state. Over the last decade, the MENA region realised that the West is an unreliable partner. The West has failed in the resolution of several files in the region: from the political instability in Libya, to Yemen, which remains one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world, to the chaotic abandoning of Afghanistan.

Many Arab leaders also note with concern that America’s “pivot to Asia” is a pivot away from the Arab region. This explains why most Arab countries have been so slow of the mark in formulating their positions vis-à-vis Russia and its war. The only immediate responses to the crisis came from Kuwait, which condemned Russia’s actions, knowing only too well what it means to be a smaller state coveted by a much larger neighbour. The UN General Assembly vote on 2 March brought a bit more clarity as to how regional states were responding: the majority of the Arab states voted in favour of the resolution which condemned Russia’s invasion, only a few abstained. However, even among the countries that voted in support of the resolution, most have continued to choose their words very carefully, refraining from explicitly condemning Russia’s actions.

The wheat crisis and its implications on the Arab countries

The challenge of responding to developments in Ukraine without undermining their friendly relations with Moscow has highlighted a dilemma for many Arab states. The Arab states fear that the current war could lead to a severe food crisis in a region already under pressure. Non-oil producer states, such as Lebanon, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan and Yemen rely on Ukraine and/or Russia for their food imports, particularly for wheat and cereals. The crisis is set to disrupt grain and oilseeds supply chains, increase food prices, and shoot up domestic production costs in agriculture. Reduced yields and incomes, especially for small-scale farmers, will have adverse implications for livelihoods and likely disproportionately affect those, among the poor and vulnerable, who are dependent on farming for their income.

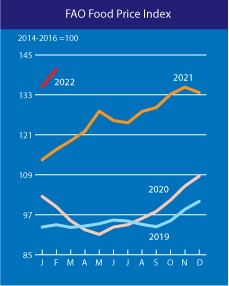

In 2011 there was one unnoticed factor that had a global impact but affected the Arab countries the most: food prices and more specifically the rising price of grain. The main trigger of the Arab Spring was the rising price of the grain. In the last weeks, the FAO Food Price Index (A measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities) averaged 140.7 points in February 2022, up 5.3 points (3.9 percent) from January and as much as 24.1 points (20.7 percent) above its level a year ago.

Release date: 04/03/2022

Source: FAO website

The level of FAO Food Price index reached today represents a new all-time high, exceeding the previous top of February 2011 by 3.1 points. Why is this index so important for Arab countries? Because the Arab countries account for one-third of worldwide wheat imports. The Arab Spring in 2011 took place in the context of the highest ever increase of the Food Price index in the last 40 years. The current situation in every non-oil producer Arab state seems to be very similar to the period pre-Arab Spring in 2011. If the Arab governments with the assistance of World Bank, will be unable to address the rise of food prices and especially the price of the grain, just a few weeks before the beginning of Ramadan, the Arab region could experience again a new wave of protests which would lead to a political turmoil.

Conclusions

The Ukraine war has already affected several sectors critical to the economies of the Arab states, from oil and gas to agricultural imports and tourism. Further fallout could increase instability in the region and beyond. However, the most problematic issue that the region is facing is related to the price of wheat. Some Arab countries grow wheat themselves, but domestic production doesn’t fully cover overall demand. Moreover, with access to the Mediterranean Sea, Arab countries could try to import wheat from other countries, but such alternatives can’t fully replace Russian and Ukrainian imports.

The recent history of the Food Riots in the Middle East has taught us that as analysts we have to pay attention and monitor constantly the price of the grain in this region in order to predict where political instability, revolution, coups d’état or interstate warfare will occur.

The Arab world’s moment of choice

By Emanuel Pietrobon

The news went unnoticed in Italy, where the media system is completely and literally focused on Ukraine, but the Arab world – and several other geopolitical regions – is playing a key-role in this conflict.

This war is going to be remembered by posterity as the watershed moment of what political scientists use to call the great power competition, of what journalists have defined the Cold War 2.0., and of what Pope Francis named the “piecemal World War Three” in 2014.

Popes, bridge-builders and God-gifted clairvoyant strategists par excellence, they always had and have a much clearer vision than the crowd. They see what others can’t. The Ukraine war is the self-proving evidence that the Pope was right: he rightly read Euromaidan not as a single event, but a key-part of a large-scale conflict for world hegemony. History proved him right. The world is in Ukraine.

For Russia the time has come to start reaping after years of sowing: thousands of foreign fighters are being recruited from Central African Republica to Syria, sanctions are no longer seen as a life-threatening risk but as an opportunity to speed up the building of a bullet-proof resistance economy, a heterogeneous number of partners are backing the Kremlin’s in several ways.

The MENA region is no exception. Saudi Arabia and UAE declined calls with Biden and rejected an American offer that only some years ago would have been considered irrefutable – the increase in oil production to contain the price and help the West cope with the war-related energy crisis. Saudi Arabia, after refusing the Biden administration’s (ir)refutable offer, confirmed the existence of epoch-making talks with the People’s Republic of China on oil sales in yuan.

Gas-rich Qatar claimed that it has no capacity to help the EU replace Russian gas. Lebanon is divided: the government is against the war, Hezbollah backs Russia’s moves. Jordan and Egypt are worried about the food crisis and cannot risk provoking their main source of wheat and other agricultural products: Russia.

Algeria is ready to provide the EU with more natural gas but it mustn’t be underestimated nor overlooked that the country is increasingly tied to Russia, it sees some EU countries in terms of rivalry – France – and it can read as a diplomatic affront the EU’s changing stance on Western Sahara – emblematized by Spain’s recent recognition of Moroccan plans for the half-autonomous region.

Arab countries keep relying economically on the EU and politically on the US, but they are increasingly tied to China and they look at Russia’s multipolar agenda with sympathy. The West keeps being the major player when it comes to influence over the Arab world, but that time is coming to an end – the question is not if, it’s when – and this war is likely to accelerate this trend.

The Authors

Brahim Ramli is a geopolitical analyst from Italy. He graduated in Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Geneva. He worked at NATO. He is an expert in conflicts, geopolitics and international security. He mostly deals with MENA affairs.